CITATION

Criminal Appeal No.416 OF 2018 (Arising out of Special Leave Petition (Crl.)No.5661 of 2017).

ACT

Scheduled Castes and the Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989

ISSUES

On 20th November 2017, the apex court passed an order in which the following question which arose:

- Whether any unilateral allegation of mala fide intention can be ground to prosecute officers who dealt with the matter in an official capacity and if such allegation is falsely made what is protection available against such abuse? The court said if the allegation is to be acted upon, the proceedings can result in arrest or prosecution of the person and have serious consequences on his right to liberty even on a false complaint which may not be intended by law meant for protection of a bona fide victim.

- The question is whether this will be just and fair procedure under Article 21 of the Constitution of India? Or, there can be procedural safeguards so that provisions of Scheduled Castes and the Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989 (“SC & ST PA Act”) are not abused for extraneous considerations?

FACTS OF THE CASE

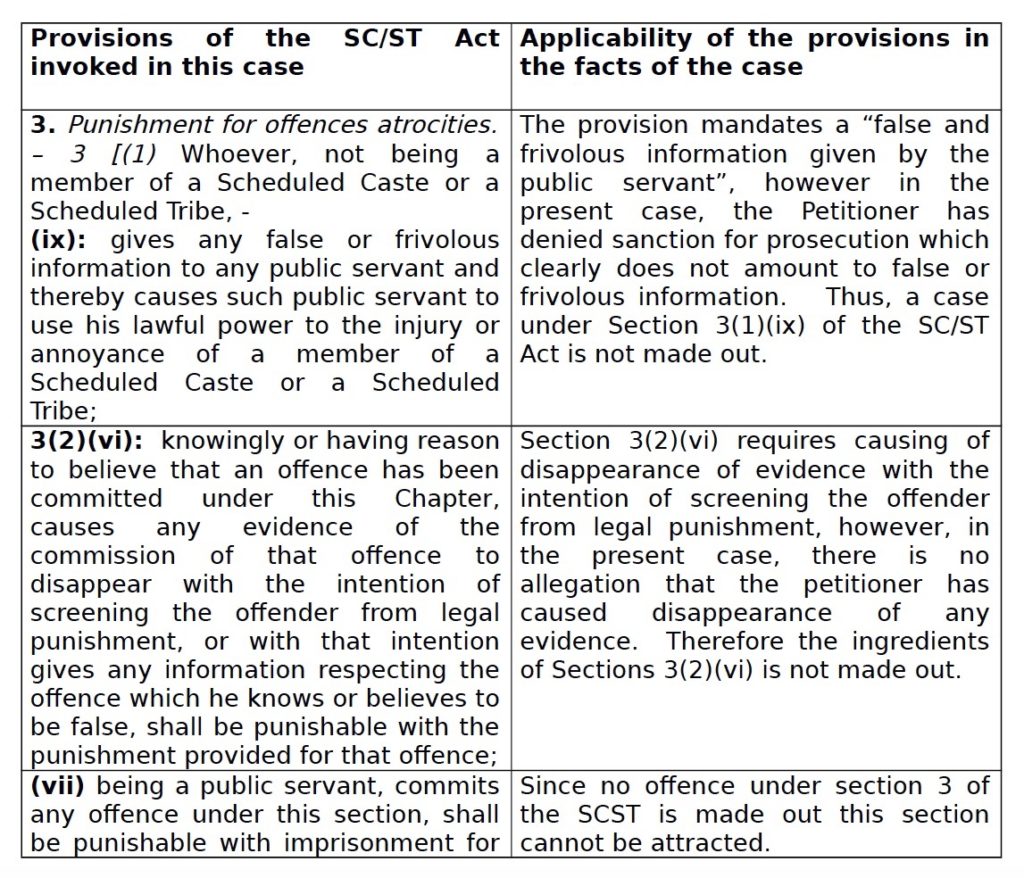

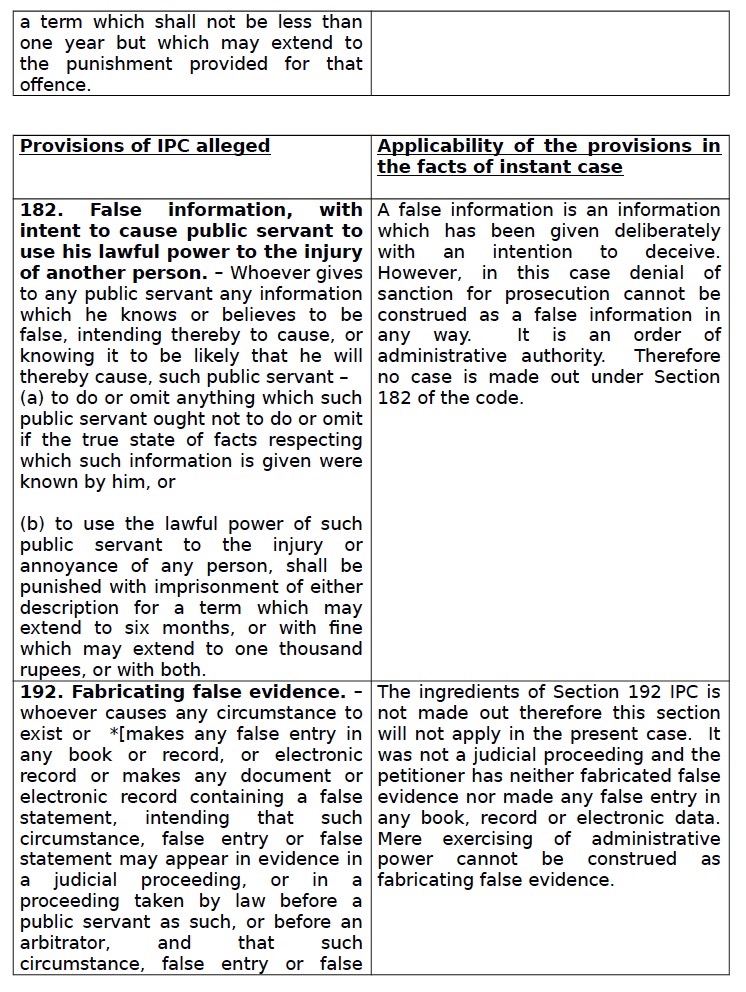

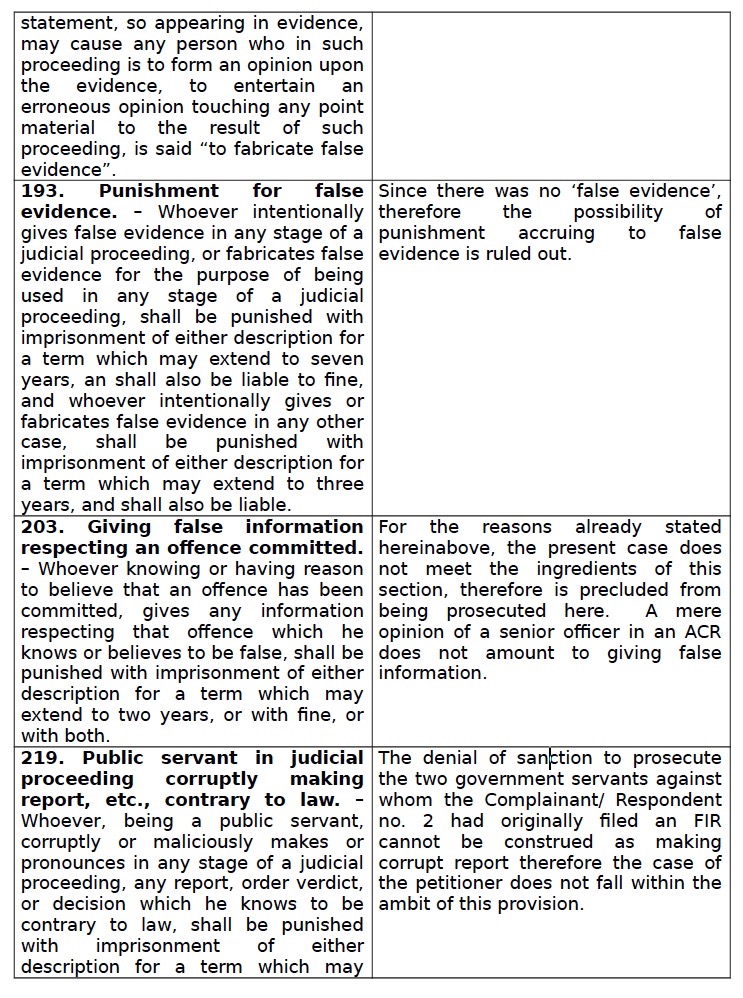

The appellant herein is the accused in the case registered at City Police Station, Karad for the offences punishable under Sections 3(1)(ix), 3(2)(vi) and 3(2)(vii) of the Scheduled Castes and the Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989 as also Sections 182, 192, 193, 203 and 219 read with 34 of the Indian Penal Code, 1860 (IPC). He was serving as Director of Technical Education in the State of Maharashtra at the relevant time.

The second respondent, the complainant is an employee of the department. He was posted at Government Distance Education Institute, Pune. Dr Satish Bhase and Dr Kishor Burade, who were his seniors but non- scheduled caste, made an adverse entry in his annual confidential report to the effect that his integrity and character was not good.

He lodged FIR with Karad Police Station against the said two officers under the Act on 4th January 2006 on that ground.

The concerned Investigating Officer applied for sanction under Section 197 Cr.P.C. against them to the Director of Technical Education on 21st December 2010.

The sanction was refused by the appellant on 20th January 2011. Because of this, C Summary Report was filed against Bhise and Burade which was not accepted by the court. He then lodged the present FIR against the appellant. According to the complainant, the Director of Technical Education was not competent to grant/refuse sanction as the above two persons are Class-I officers and only the State Government could grant sanction.

Thus, according to him, the appellant committed the offences alleged in the FIR dated 28 th March 2016 by illegally dealing with the matter of sanction.

Para 7 of the judgment: Dealing with the contention that if such cases are not quashed, recording of genuine adverse remarks against an employee who is a member of SC/ST or passing a legitimate administrative order in the discharge of official duties will become difficult and jeopardise the administration, the High Court observed that no public servant or reviewing authority need to apprehend any action by way of false or frivolous prosecution but the penal provisions of the Atrocities Act could not be faulted merely because of the possibility of abuse. It was observed that in the facts and circumstances, inherent power to quash could not be exercised as it may send a wrong signal to the downtrodden and backward sections of the society.

SUBMISSION OF AMICUS CURIE

The Amicus Curie submitted that before liberty of a person is taken away, there has to be a fair, reasonable and just procedure. Referring to Section 41(1)(b) Cr.P.C. it was submitted that arrest could be effected only if there was credible information and only if the police officer had reason to believe that the offence had been committed and that such arrest was necessary. Thus, the power of arrest should be exercised only after complying with the safeguards intended under Sections 41 and 41A Cr.P.C.

Para 14 of the judgment:

It was submitted that in the context of the Atrocities Act, in the absence of tangible material to support a version, to prevent the exercise of the arbitrary power of arrest, a preliminary enquiry may be made mandatory. Reasons should be required to be recorded that information was credible and arrest was necessary. In the case of a public servant, approval of disciplinary authority should be obtained and in other cases, approval of the Superintendent of Police should be necessary. While granting such permission, based on a preliminary enquiry, the authority granting permission should be satisfied with the credibility of the information and also about the need for arrest. If an arrest is effected, while granting remand, the Magistrate must pass a speaking order as to the correctness or otherwise of the reasons for which arrest is affected. These requirements will enforce the right of concerned citizens under Articles 14 and 21 without in any manner affecting genuine objects of the Act.

Para 15 of the judgment:

Learned amicus further submitted that Section 18 of the Atrocities Act, which excludes Section 438 Cr.P.C., violates constitutional mandate under Articles 14 and 21 and If a Court is not debarred from granting anticipatory bail even in most heinous offences including murder, rape, dacoity, robbery, NDPS, sedition etc., which are punishable with longer periods depending upon parameters for grant of anticipatory bail, taking away such power in respect of offences under the Act is discriminatory and violative of Article 14. Exclusion of the court’s jurisdiction, even where the court is satisfied that arrest of a person was not called for, has no nexus with the object of the Atrocities Act

ARTICLE 21 OF THE CONSTITUTION OF INDIA

In para 33. Constitution Bench of this Court mentioned observations in Union of India versus Raghubir Singh (1989(2) SCC 754, observed :

“7. … It used to be disputed that Judges make law. Today, it is no longer a matter of doubt that a substantial volume of the law governing the lives of citizens and regulating the functions of the State flows from the decisions of the superior Courts. “There was a time,” observed Lord Reid, “When it was thought almost indecent to suggest that Judges make law – They only declare it… But we do not believe in fairy tales any more.” “The Judge as Law Maker”, p. 22. In countries such as the United Kingdom, where Parliament as the legislative organ is supreme and stands at the apex of the constitutional structure of the State, the role played by judicial law-making is limited.

In the first place, the function of the Courts is restricted to the interpretation of laws made by Parliament, and the Courts have no power to question the validity of Parliamentary statutes, the Diceyan dictum holding true that the British Parliament is paramount and all-powerful. In the second place, the law enunciated in every decision of the Courts in England can be superseded by an Act of Parliament. As Cockburn C.J. observed in Exp. Canon Selwyn (1872) 36 JP Jo 54: There is no judicial body in the country by which the validity of an Act of Parliament could be questioned. An act of the Legislature is superior in authority to any Court of Law.

And Ungoed Thomas J., in Cheney v. Conn, (1968) 1 All ER 779 referred to a Parliamentary statute as “the highest form of law…which prevails over every other form of law.” The position is substantially different under a written Constitution such as the one which governs us. The Constitution of India, which represents the Supreme Law of the land, envisages three distinct organs of the State, each with its own distinctive functions, each a pillar of the State.

Broadly, while Parliament and the State Legislature fin India enact the law and the Executive Government implements it, the judiciary sits in judgment not only on the implementation of the law by the Executive but also on the validity of the Legislation sought to be implemented One of the functions of the superior judiciary in India is to examine the competence and validity of legislation, both in point of legislative competence as well as its consistency with the Fundamental Rights. In this regard, the Courts in India possess a power not known to the English Courts. Where a statute is declared invalid in India it cannot be reinstated unless constitutional sanction is obtained therefore by a constitutional amendment of an appropriately modified version of the statute is enacted which accords with a constitutional prescription.

The range of judicial, review recognised in the superior judiciary of India is perhaps the widest and the most extensive known to the world of law.

The power extends to examining the validity of even an amendment to the Constitution, for now, it has been repeatedly held that no constitutional amendment can be sustained which [violates the basic structure of the Constitution. See Kesavananda Bharati Sripadagalayaru v. State of Kerala AIR1973SC1461), Smt. Indira Nehru. Gandhi v. Raj Narain [1976]2SCR347], Minerva Mills Ltd. v. Union of India [1981]1SCR206] and recently in S. P. Sampath Kumar v. Union of India [(1987)ILLJ128SC]. With this impressive expanse of judicial power, it is only right that the superior Courts in India should be conscious of the enormous responsibility which rests on them. This is specially true of the Supreme Court, for as the highest Court in the entire judicial system the law declared by it is, by Article 141 of the Constitution, binding on« all Courts within the territory of India.”

Para 34: The law has been summed up in a decision in Rajesh Kumar versus State (2011) 13 SCC 706 as follows:

“62. Until the decision was rendered in Maneka Gandhi (supra), Article 21 was viewed by this Court as rarely embodying the Diceyian concept of rule of law that no one can be deprived of his personal liberty by an executive action unsupported by law. If there was a law which provided some sort of a procedure it was enough to deprive a person of his life or personal liberty. In this connection, if we refer to the example given by Justice S.R. Das in his judgment in A.K. Gopalan (supra) that if the law provided the Bishop of Rochester ‘be boiled in oil’ it would be valid under Article 21. But after the decision in Maneka Gandhi (supra) which marks a watershed in the development of constitutional law in our country, this Court, for the first time, took the view that Article 21 affords protection not only against the executive action but also against the legislation which deprives a person of his life and personal liberty unless the law for deprivation is reasonable, just and fair. and it was held that the concept of reasonableness runs like a golden thread through the entire fabric of the Constitution and it is not enough for the law to provide some semblance of a procedure. The procedure for depriving a person of his life and personal liberty must be eminently just, reasonable and fair and if challenged before the Court it is for the Court to determine whether such procedure is reasonable, just and fair and if the Court finds that it is not so, the Court will strike down the same.”

PRESUMPTION OF INNOCENCE

65. Presumption of innocence is a human right. No doubt, placing of the burden of proof on accused in certain circumstances may be permissible but there cannot be a presumption of guilt so as to deprive a person of his liberty without an opportunity before an independent forum or Court. In Noor Aga versus the State of Punjab (2008) 16 SCC 417, it was observed:

“33. Presumption of innocence is a human right as envisaged under Article 14(2) of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. It, however, cannot per se be equated with the fundamental right and liberty adumbrated in Article 21 of the Constitution of India. It, having regard to the extent thereof, would not militate against other statutory provisions (which, of course, must be read in the light of the constitutional guarantees as adumbrated in Articles 20 and 21 of the Constitution of India).

xxxx xxxx xxxx

35. A right to be presumed innocent, subject to the establishment of certain foundational facts and burden of proof, to a certain extent, can be placed on an accused. It must be construed having regard to the other international conventions and having regard to the fact that it has been held to be constitutional. Thus, a statute may be constitutional but a prosecution thereunder may not be held to be one. Indisputably, civil liberties and rights of citizens must be upheld.

Xxxx xxxx xxxx

43. The issue of reverse burden vis-à-vis the human rights regime must also be noticed. The approach of the common law is that it is the duty of the prosecution to prove a person guilty. Indisputably, this common law principle was subject to parliamentary legislation to the contrary. The concern now shown worldwide is that Parliaments had frequently been making inroads on the basic presumption of innocence. Unfortunately, unlike other countries, no systematic study has been made in India as to how many offences are triable in the court where the legal burden is on the accused. In the United Kingdom, it is stated that about 40% of the offences triable in the Crown Court appear to violate the presumption. (See “The Presumption of Innocence in English Criminal Law”, 1996, CRIM. L. REV. 306, at p. 309.)

44. In Article 11(1) of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) it is stated:

“Everyone charged with a penal offence has the right to be presumed innocent until proved guilty according to law….” Similar provisions have been made in Article 6.2 of the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (1950) and Article 14.2 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (1966).

Xxx xxxx xxx xxx

47. We may notice that Sachs, J. in State v. Coetzee [1997(2) LRC 593] explained the significance of the presumption of innocence in the following terms:

“There is a paradox at the heart of all criminal procedure in that the more serious the crime and the greater the public interest in securing convictions of the guilty, the more important do constitutional protections of the accused become. The starting point of any balancing enquiry where constitutional rights are concerned must be that the public interest in ensuring that innocent people are not convicted and subjected to ignominy and heavy sentences massively outweighs the public interest in ensuring that a particular criminal is brought to book.

… Hence the presumption of innocence, which serves not only to protect a particular individual on trial but to maintain public confidence in the enduring integrity and security of the legal system. Reference to the prevalence and severity of a certain crime, therefore, does not add anything new or special to the balancing exercise. The perniciousness of the offence is one of the givens, against which the presumption of innocence is pitted from the beginning, not a new element to be put into the scales as part of a justificatory balancing exercise. If this were not so, the ubiquity and ugliness argument could be used in relation to murder, rape, car-jacking, housebreaking, drug-smuggling, corruption … the list is unfortunately almost endless, and nothing would be left of the presumption of innocence, save, perhaps, for its relic status as a doughty defender of rights in the most trivial of cases.”

POINTERS OF THE JUDGMENT

- The apex court observed that jurisdiction of the Court to issue appropriate orders or directions for enforcement of fundamental rights is a basic feature of the Constitution. Supreme court is the interpreter of the Constitution, it is the duty of the court to uphold the constitutional rights and values. Articles 14, 19 and 21 represent the foundational values which form the basis of the rule of law.

- Right to equality and life and liberty has to be protected against any unreasonable procedure, even if it is enacted by the legislature. The substantive, as well as procedural laws, must conform to Articles 14 and 21.

- Court citing Maneka Gandhi vs. UOI (1978) 1 SCC 248 said that it is very important to find new tools and strategies to protect fundamental rights, no procedural technicality can stand in between enforcement of fundamental rights.

- The power extends to examining the validity of even an amendment to the Constitution, for now, it has been repeatedly held that no constitutional amendment can be sustained which violates the basic structure of the Constitution.

- Article 21 of the constitution of India provides protection of life and personal liberty: No person shall be deprived of personal liberty except according to the procedure established by law. Supreme Court while interpreting article 21 in Maneka Gandhi’s case widened the scope of personal liberty. The procedure established by law cannot be arbitrary, unfair, or unreasonable.

SUPREME COURT DIRECTIONS ON ARREST

In D.K. Basu versus the State of W.B.44, the apex Court, to check abuse of arrest and drastic police power, directed as follows: (1997) 1 SCC 416 35.

We, therefore, consider it appropriate to issue the following requirements to be followed in all cases of arrest or detention till legal provisions are made in that behalf as preventive measures: (1) The police personnel carrying out the arrest and handling the interrogation of the arrestee should bear accurate, visible and clear identification and name tags with their designations. particulars of all such police personnel who handle interrogation of the arrestee must be recorded in a register.

(2) That the police officer carrying out the arrest of the arrestee shall prepare a memo of arrest at the time of arrest and such memo shall be attested by at least one witness, who may either be a member of the family of the arrestee or a respectable person of the locality from where the arrest is made. It shall also be countersigned by the arrestee and shall contain the time and date of arrest.

(3) A person who has been arrested or detained and is being held in custody in a police station or interrogation centre or other lock-up shall be entitled to have one friend or relative or other person known to him or having an interest in his welfare being informed, as soon as practicable, that he has been arrested and is being detained at the particular place unless the attesting witness of the memo of arrest is himself such a friend or a relative of the arrestee.

(4) The time, place of arrest and venue of custody of an arrestee must be notified by the police where the next friend or relative of the arrestee lives outside the district or town through the Legal Aid Organisation in the District and the police station of the area concerned telegraphically within a period of 8 to 12 hours after the arrest.

(5) The person arrested must be made aware of this right to have someone informed of his arrest or detention as soon as he is put under arrest or is detained.

(6) An entry must be made in the diary at the place of detention regarding the arrest of the person which shall also disclose the name of the next friend of the person who has been informed of the arrest and the names and particulars of the police officials in whose custody the arrestee is.

(7) The arrestee should, where he so requests, be also examined at the time of his arrest and major and minor injuries, if any present on his/her body, must be recorded at that time. The Inspection Memo must be signed both by the arrestee and the police officer effecting the arrest and its copy provided to the arrestee.

(8) The arrestee should be subjected to a medical examination by a trained doctor every 48 hours during his detention in custody by a doctor on the panel of approved doctors appointed by Director, Health Services of the State or Union Territory concerned. Director, Health Services should prepare such a panel for all tehsils and districts as well.

(9) Copies of all the documents including the memo of arrest, referred to above, should be sent to the Magistrate for his record.

(10) The arrestee may be permitted to meet his lawyer during interrogation, though not throughout the interrogation.

(11) A police control room should be provided at all district and State headquarters, where information regarding the arrest and the place of custody of the arrestee shall be communicated by the officer causing the arrest, within 12 hours of effecting the arrest and at the police control room it should be displayed on a conspicuous notice board.

The court held that failure to comply with the requirements above mentioned shall apart from rendering the official concern liable for departmental action, also render him liable to be punished for contempt of court and the proceedings for contempt of court may be instituted in any High Court of the country, having territorial jurisdiction over the matter.

GUIDELINES ON ANTICIPATORY BAIL

The while citing the Siddharam Satlingappa Mhetre versus State of Maharashtra judgment laid down guidelines for the exercise of discretion of anticipatory bail courts should keep in mind the fundamental right of liberty under Article 21 of the Constitution and the needs of the society where such liberty may be required to be taken away. The court referred to inter alia Para 112 of the judgment.

-

- The following factors and parameters can be taken into consideration while dealing with the anticipatory bail:

(i) The nature and gravity of the accusation and the exact role of the accused must be properly comprehended before arrest is made;

(ii) The antecedents of the applicant including the fact as to whether the accused has previously undergone imprisonment on conviction by a court in respect of any cognizable offence;

(iii) The possibility of the applicant to flee from justice;

(iv) The possibility of the accused likelihood to repeat similar or other offences;

(v) Where the accusations have been made only with the object of injuring or humiliating the applicant by arresting him or her;

(vi) Impact of grant of anticipatory bail particularly in cases of large magnitude affecting a very large number of people;

(vii) The courts must evaluate the entire available material against the accused very carefully. The court must also clearly comprehend the exact role of the accused in the case. The cases in which the accused is implicated with the help of Sections 34 and 149 of the Penal Code, 1860 the court should consider with even greater care and caution because over implication in the cases is a matter of common knowledge and concern;

(viii) While considering the prayer for grant of anticipatory bail, a balance has to be struck between two factors, namely, no prejudice should be caused to the free, fair and full investigation and there should be the prevention of harassment, humiliation and unjustified detention of the accused;

(ix) The court to consider reasonable apprehension of tampering of the witness or apprehension of threat to the complainant;

(x) Frivolity in prosecution should always be considered and it is only the element of genuineness that shall have to be considered in the matter of grant of bail and in the event of there being some doubt as to the genuineness of the prosecution, in the normal course of events, the accused is entitled to an order of bail.

Section 18 of the SC & ST PA Act containing bar against grant of anticipatory bail is as follows: Section 438 of the Code not to apply to persons committing an offence under the Act. Nothing in Section 438 of the Code shall apply in relation to any case involving the arrest of any person on an accusation of having committed an offence under this Act.

CONCEPT OF INTERIM BAIL

69. In Lal Kamlendra Pratap(supra), this Court held that even if there is no provision for anticipatory bail, the Court can grant interim bail in suitable cases. It was observed :

“6. Learned counsel for the appellant apprehends that the appellant will be arrested as there is no provision for an anticipatory bail in the State of U.P. He placed reliance on a decision of the Allahabad High Court in Amarawati v. State of U.P. [2005 Crl LJ 755 (All)] in which a seven-judge Full Bench of the Allahabad High Court held that the court if it deems fit in the facts and circumstances of the case, may grant interim bail pending final disposal of the bail application. The Full Bench also observed that arrest is not a must whenever an FIR of a cognizable offence is lodged. The Full Bench placed reliance on the decision of this Court in Joginder Kumar v. the State of U.P.[(1992) 4 SCC 260]

7. We fully agree with the view of the High Court in Amarawati case and we direct that the said decision be followed by all courts in U.P. in letter and spirit, particularly since the provision for anticipatory bail does not exist in U.P.

8. Inappropriate cases interim bail should be granted pending disposal of the final bail application since arrest and detention of a person can cause irreparable loss to a person’s reputation, as held by this Court in Joginder Kumar case. Also, an arrest is not a must in all cases of cognizable offences, and in deciding whether to arrest or not the police officer must be guided and act according to the principles laid down in Joginder Kumar case.”

THE DECISION OF THE SUPREME COURT IN SUBHASH KASHINATH

The apex court in para 79-80 held that they are of the view that cases under the SC & ST PA Act also fall in the exceptional category where preliminary inquiry must be held. Such inquiry must be time-bound and should not exceed seven days in view of directions in Lalita Kumari (2014) 2 SCC 1.

Even if a preliminary inquiry is held and the case is registered, an arrest is not a must as we have already noted. In Lalita Kumari (supra) it was observed :

“107. While registration of FIR is mandatory, the arrest of the accused immediately on registration of FIR is not at all mandatory. In fact, registration of FIR and arrest of an accused person are two entirely different concepts under the law, and there are several safeguards available against arrest. Moreover, it is also pertinent to mention that an accused person also has a right to apply for “anticipatory bail” under the provisions of Section 438 of the Code if the conditions mentioned therein are satisfied. Thus, in appropriate cases, he can avoid the arrest under that provision by obtaining an order from the court.”

“115. Although, we, in unequivocal terms, hold that Section 154 of the Code postulates the mandatory registration of FIRs on receipt of all cognizable offences, yet, there may be instances where preliminary inquiry may be required owing to the change in genesis and novelty of crimes with the passage of time. One such instance is in the case of allegations relating to medical negligence on the part of doctors. It will be unfair and inequitable to prosecute a medical professional only on the basis of the allegations in the complaint.

xxxx xxxx xxxx

117. In the context of offences relating to corruption, this Court in P. Sirajuddin [(1970) 1 SCC 595] expressed the need for a preliminary inquiry before proceeding against public servants.

xxxx xxxx xxxx

120.6. As to what type and in which cases preliminary inquiry is to be conducted will depend on the facts and circumstances of each case. The category of cases in which preliminary inquiry may be made are as under:

(a) Matrimonial disputes/family disputes

(b) Commercial offences

(c) Medical negligence cases

(d) Corruption cases

(e) Cases where there is abnormal delay/laches in initiating criminal prosecution, for example, over 3 months’ delay in reporting the matter without satisfactorily explaining the reasons for the delay.

The aforesaid are only illustrations and not exhaustive of all conditions which may warrant preliminary inquiry.

120.7. While ensuring and protecting the rights of the accused and the complainant, a preliminary inquiry should be made time-bound and in any case, it should not exceed 7 days. The fact of such delay and the causes of it must be reflected in the General Diary entry.”

CONCLUSIONS IN THE JUDGMENT

Conclusions are as follows mentioned in the judgment:

i) Proceedings in the present case are a clear abuse of process of court and are quashed.

ii) There is no absolute bar against grant of anticipatory bail in cases under the Atrocities Act if no prima facie case is made out or where on judicial scrutiny the complaint is found to be prima facie mala fide. We approve the view taken and approach of the Gujarat High Court in Pankaj D Suthar (supra) and Dr N.T. Desai (supra) and clarify the judgments of this Court in Balothia (supra) Manju Devi (supra);

iii) In view of acknowledged abuse of law of arrest in cases under the Atrocities Act, the arrest of a public servant can only be after approval of the appointing authority and of a non-public servant after approval by the S.S.P. which may be granted in appropriate cases if considered necessary for reasons recorded. Such reasons must be scrutinized by the Magistrate for permitting further detention.

iv) To avoid false implication of an innocent, a preliminary enquiry may be conducted by the DSP concerned to find out whether the allegations make out a case under the Atrocities Act and that the allegations are not frivolous or motivated.

v) Any violation of direction (iii) and (iv) will be actionable by way of disciplinary action as well as contempt. The above directions are prospective.

RECENT AMENDMENTS IN THE SC & ST PA ACT

However, a new section was added in the Act by SC and ST (Prevention of Atrocities Act ) Amendment Act,2018

Section 18A (1) for the purpose of this Act,-

(a) The preliminary enquiry shall not be required for registration of a first information report against any person; or

(b) The investigating officer shall not require approval for the arrest, if necessary of any person,

Against whom an accusation of having committed an offence under this Act has been made and no procedure other than that provided under this Act or the code shall apply.

(2) the provisions of section 438 of the code shall not apply to any case under this act, notwithstanding any judgment or order or direction of any court.

Later on, a case of PRATHVI RAJ CHAUHAN v UNION OF INDIA & ORS 2020 SCC Online SC 159, the validity of the amended section 18A was raised and the provision was upheld by the Hon’ble Court.

LEGAL RESEARCHER AND CO-AUTHOR MEGHA SINGH BA.LLB, 4TH YEAR Intern, Indian Law Watch

Add Comment